R Kym Horsell

2016-05-06 07:46:41 UTC

Forest fires, coral bleaching -- what's sommin else that will never happen?

...

Oh, here's one.

<http://e360.yale.edu/feature/

abrupt_sea_level_rise_realistic_greenland_antarctica/2990>

Abrupt Sea Level Rise Looms As Increasingly Realistic Threat [in color]

nicola jones

05 May 2016

[Image] Ninety-nine percent of the planet's freshwater ice is locked

up in the Antarctic and Greenland ice caps. Now, a growing number of

studies are raising the possibility that as those ice sheets melt, sea

levels could rise by six feet this century, and far higher in the

next, flooding many of the world's populated coastal areas.

West Antarctica's glaciers and floating ice shelves are becoming

increasingly unstable.

Last month in Greenland, more than a tenth of the ice sheet's surface

was melting in the unseasonably warm spring sun, smashing 2010's

record for a thaw so early in the year. In the Antarctic, warm water

licking at the base of the continent's western ice sheet is, in

effect, dissolving the cork that holds back the flow of glaciers into

the sea; ice is now seeping like wine from a toppled bottle.

The planet's polar ice is melting fast, and recent satellite data,

models, and fieldwork have left scientists sobered by the speed of the

sea level rise we should expect over the coming decades. Although

researchers have long projected that the planet's biggest ice sheets

and glaciers will wilt in the face of rising temperatures, estimates

of the rate of that change keep going up. When the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put out its last report in 2013, the

consensus was for under a meter (3.3 feet) of sea level rise by

2100. In just the last few years, at least one modeling study suggests

we might need to double that.

Eric Rignot at the University of California, Irvine says that study

underscores the possible speed of ice sheet melt and collapse. "Once

these processes start to kick in," he says, "they're very fast."

The Earth has seen sudden climate change and rapid sea level rise

before. At the end of the planet's last glaciation, starting about

14,000 years ago, sea levels rose by more than 13 feet a century as

the huge North American ice sheet melted.

Greenland is losing some 200 billion tons of ice each year. That rate

doubled from the 1900s to the 2000s.

But researchers are hesitant about predicting similarly rapid climate

shifts in our future given the huge stakes involved: The rapid

collapse of today's polar ice sheets would erase densely populated

parts of our coastlines.

"Today, we're struggling with 3 millimeters [0.1 inch] per year [of

sea level rise]," says Robert DeConto at the University of

Massachusetts-Amherst, co-author of one of the more sobering new

studies. "We're talking about centimeters per year. That's really

tough. At that point your engineering can't keep up; you're down to

demolition and rebuilding."

Antarctica and Greenland hold the overwhelming majority of the world's

ice: Ninety percent of the planet's freshwater ice is locked up in

Antarctica's ice cap and nine percent in Greenland's. Today, the ice

sheet that's inarguably melting fastest is Greenland. That giant block

of ice, which has the potential to raise global sea levels by 23 feet

if it melts in its entirety, is losing some 200 billion tons of ice

each year. That rate has doubled from the 1900s to the 2000s.

"We are seeing changes in Greenland in all four corners, even in the

far north," says Rignot. Many of the outlet glaciers that flow down

fjords into the sea, which were "on the fence" about retreating or

advancing over the past decade, are now "starting to fall apart," he

says.

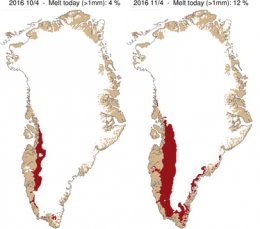

Danish Meteorological Institute

<Loading Image... >

>

Illustration of the rapid expansion of ice melt on Greenland over just

two days in April 2016.

And they're moving fast. "The flow speeds we talk about today would

have been jaw-dropping in the 1990s," says Ted Scambos of the

University of Colorado's National Snow and Ice Data

Center. Greenland's Jakobshavn Glacier dumped ice into the sea at the

astonishing rate of 150 feet per day in the summer of 2012. The most

dramatic action in Greenland is simply from surface melting, as

temperatures there and across the Arctic have soared in the last four

decades. In 2012, Greenland lost a record 562 billion tons of ice as

more than 90 percent of its surface melted in the summer sun.

Many questions remain about the physics of Greenland's ice loss, such

as whether meltwater gets soaked up by a `sponge' of snow and ice, or

trickles down to lubricate the base of the ice sheet and speed its

seaward movement. Most modeling work has been about how Greenland's

melt tracks rising air temperatures; far less is known about how

warming waters might eat away at the edges of its ice sheet. Rignot is

part of a team now launching the Oceans Melting Greenland project

(with the intentionally punny acronym OMG) to investigate that. These

uncertainties make Rignot think that estimates of Greenland's melt -

contributing as much as 9 inches of global sea level rise by 2100,

according to the 2013 IPCC report - have been far too

conservative. Assuming that the Greenland ice sheet's demise "will be

slow is wishful thinking," Rignot says.

But most scientists say there shouldn't be too many serious surprises

about the physics governing Greenland's ice loss. Although the ice

sheet can be expected to steadily melt in the face of rising

temperatures, Greenland's ice cap shouldn't rapidly collapse, because

most of its ice sits safely on rock far above sea level. "Greenland is

more predictable and straightforward," says DeConto.

For fear of rapid, runaway collapse, the research community turns its

eyes south.

Antarctica is, for now, losing ice more slowly than Greenland. The

latest data from the GRACE project - twin satellites that measure mass

using gravity data - say Antarctica is losing about 92 billion tons of

ice per year, with that rate having doubled from 2003 to 2014.

The sizeable western half of Antarctica holds some of the

fastest-warming areas on the planet.

But Antarctica is vast - 1.5 times the size of the United States, with

ice three miles thick in places - and holds enough ice to raise global

sea levels by roughly 200 feet.

The larger, eastern half lies mostly above sea level and remains very

cold; researchers have typically considered its ice stable, though

even that view is beginning to change. The sizeable western half of

the Antarctic, by contrast, has its base lying below sea level, and

holds some of the fastest warming areas on the planet. "You look at

West Antarctica and you think: How come it's still there?" says

Rignot.

Warming ocean water licking at the underside of the floating edges of

the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet is eating away at the line where the

ice rests on solid rock. Much of the bedrock of the Antarctic slopes

downward toward the center of the continent, so as the invading water

flows downhill it seeps further and further inland, causing

ever-larger chunks of glaciers to flow faster into the sea. This

so-called "grounding line" has been eroding inland rapidly, in some

parts of West Antarctica at rates of miles per year. In 2014,

satellite radar images revealed just how vulnerable five massive

glaciers flowing into the Admundsen Sea are from this effect. And a

2015 paper showed that the same thing is happening more slowly to

Totten Glacier, one of the biggest glaciers in the east.

Such dramatic processes have been the bane of Antarctic modeling and

the reason why scientists have been loathe to put a number on sea

level contributions from a melting southern continent. Then in March

came a report in Nature that some say represents a step change in our

ability to do that. DeConto and David Pollard of Pennsylvania State

University put into their ice sheet model two basic phenomena:

meltwater trickling down to lubricate glacier flow, and giant walls of

ice (created when the ends of glaciers snap off) simply collapsing

under their own weight. These new modeling parameters gave DeConto and

Pollard a better understanding of past sea level rise events. For the

Pliocene era 3 million years ago, for example - when seas were dozens

of feet higher than today - older models estimated that a partially

melting Antarctic added about 23 feet to global sea level rise. The

new model increased Antarctica's contribution to sea level rise during

the Pliocene to 56 feet.

<Loading Image... >

>

Satellite image showing sediment plumes from meltwater exiting

glaciers in Greenland.

Turning their model to the future, DeConto and Pollard project more than

three feet of sea level rise from Antarctica alone by 2100 - assuming

growing greenhouse gas emissions that boost the planet's temperature by

about 4 degrees C (7 degrees F). That is far more than the last IPCC

estimate in 2013, which projected less than eight inches of sea level rise

from a melting Antarctic by 2100, with a possibility for inches more from

the dramatic collapse of Antarctic glaciers.

Even DeConto admits that, under the model used in his paper, the timing and

pace of Antarctica's ice loss is "really uncertain" - it could be a decade

or two, or three or four, before these dramatic processes start to kick in,

he says. "The paper just shows the potentials, which are really big and

really scary," says DeConto. But Scambos and other observers call DeConto's

numbers "perfectly plausible."

Researchers could better pin down their models if they could track the rate

of sea level rise from polar ice sheet collapse in the past, but this has

proven hard to do. When seas rose a whopping 13 feet per century at the end

of the last glaciation (the current record-holder for known rates of sea

level rise in the past), much of the water came from an ice sheet over North

America, where there isn't one today. "I wouldn't use that as an analogue

for the future," says paleo-geologist Andrea Dutton of the University of

Florida, who wrote a recent review of past records of sea level rise. "But

it has important lessons for us nonetheless - that ice sheets can retreat

suddenly and in steps instead of gradually."

For a better analogue of what's going on today, researchers often look to

the last interglacial period, about 120,000 years ago, when temperatures

were about a degree warmer than pre-industrial levels and seas were 20 to 30

feet higher than today. Ice cores from Greenland have suggested that much of

that water must have come from the Antarctic. To find out just how fast sea

levels rose at that time, Dutton is now looking at old corals in Mexico,

Florida, and Australia; corals can be used to track sea level, since they

grow in shallow waters to capture sunlight.

--

Tesla Just Made Its Huge Model 3 Challenge Even Huger

WIRED, 05 May 2016 18:30Z

Elon Musk moved his desk. He now sits at the end of the production line at

Tesla Motors' factory in Fremont, California, and he's stashed a sleeping

bag in a nearby conference room.

Opinion:Tesla investors better be ready for wild ride -- CNBC

In Depth:Elon Musk Keeps Promising the Impossible. I Think I Know Why.

-- Slate Magazine

Winnipeg weather record set with 33-degree scorcher

CBC.ca, 05 May 2016 19:25Z

Winnipeg set a hot weather record on Thursday, when the mercury climbed to

33.2 C before 2 p.m.. The previous warm weather record for May 5 was set in

1926, when it was 31.7 C. The heat wave won't last long, though;

temperatures are expected to fall ...

Winnipeg hits 33 C, previous warm-weather record for May 5 was 31.7 C

CBC.ca, 05 May 2016 20:21Z

Manitoba broke 22 hot weather records Thursday, with the mercury climbing to

34.9 C in Winnipeg alone, making it the warmest place in Canada.

Alberta Declares State Of Emergency As Thousands Flee Massive Wildfire

ClimateProgress, 06 May 2016 8:18am

The Canadian province of Alberta declared a state of emergency Wednesday as

88,000 people in the city of Fort McMurray were forced to flee a fast-moving,

immense wildfire. The blaze has already destroyed 1,600 buildings, including

a school...

cold, rainy weather welcome after Tasmania's driest April on record

ABC Online, 05 May 2016 22:22Z

This week's rain has come with dam levels at 13 per cent after the driest

April on record. Hydro Tasmania has been drawing heavily on its storages

while the disabled Basslink electricity interconnector was not able to

import power.

'Armored Closet' Offers Tornado Safety Inside Your Home

CBS Local, 06 May 2016 03:23Z

Fort Worth (CBSDFW.COM). Depending on the home, it can be a challenge to

find a "safe-spot" during a tornado warning in North Texas.

More corals die in northern Great Barrier Reef

[Image] Coral bleached white in shallow waters off Lizard Island in the

Great Barrier Reef

ABC News, 06 May 2016 07:02Z

More coral has bleached and died in the northern section of the Great

Barrier Reef in the past month, new surveys reveal.

...

Oh, here's one.

<http://e360.yale.edu/feature/

abrupt_sea_level_rise_realistic_greenland_antarctica/2990>

Abrupt Sea Level Rise Looms As Increasingly Realistic Threat [in color]

nicola jones

05 May 2016

[Image] Ninety-nine percent of the planet's freshwater ice is locked

up in the Antarctic and Greenland ice caps. Now, a growing number of

studies are raising the possibility that as those ice sheets melt, sea

levels could rise by six feet this century, and far higher in the

next, flooding many of the world's populated coastal areas.

West Antarctica's glaciers and floating ice shelves are becoming

increasingly unstable.

Last month in Greenland, more than a tenth of the ice sheet's surface

was melting in the unseasonably warm spring sun, smashing 2010's

record for a thaw so early in the year. In the Antarctic, warm water

licking at the base of the continent's western ice sheet is, in

effect, dissolving the cork that holds back the flow of glaciers into

the sea; ice is now seeping like wine from a toppled bottle.

The planet's polar ice is melting fast, and recent satellite data,

models, and fieldwork have left scientists sobered by the speed of the

sea level rise we should expect over the coming decades. Although

researchers have long projected that the planet's biggest ice sheets

and glaciers will wilt in the face of rising temperatures, estimates

of the rate of that change keep going up. When the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put out its last report in 2013, the

consensus was for under a meter (3.3 feet) of sea level rise by

2100. In just the last few years, at least one modeling study suggests

we might need to double that.

Eric Rignot at the University of California, Irvine says that study

underscores the possible speed of ice sheet melt and collapse. "Once

these processes start to kick in," he says, "they're very fast."

The Earth has seen sudden climate change and rapid sea level rise

before. At the end of the planet's last glaciation, starting about

14,000 years ago, sea levels rose by more than 13 feet a century as

the huge North American ice sheet melted.

Greenland is losing some 200 billion tons of ice each year. That rate

doubled from the 1900s to the 2000s.

But researchers are hesitant about predicting similarly rapid climate

shifts in our future given the huge stakes involved: The rapid

collapse of today's polar ice sheets would erase densely populated

parts of our coastlines.

"Today, we're struggling with 3 millimeters [0.1 inch] per year [of

sea level rise]," says Robert DeConto at the University of

Massachusetts-Amherst, co-author of one of the more sobering new

studies. "We're talking about centimeters per year. That's really

tough. At that point your engineering can't keep up; you're down to

demolition and rebuilding."

Antarctica and Greenland hold the overwhelming majority of the world's

ice: Ninety percent of the planet's freshwater ice is locked up in

Antarctica's ice cap and nine percent in Greenland's. Today, the ice

sheet that's inarguably melting fastest is Greenland. That giant block

of ice, which has the potential to raise global sea levels by 23 feet

if it melts in its entirety, is losing some 200 billion tons of ice

each year. That rate has doubled from the 1900s to the 2000s.

"We are seeing changes in Greenland in all four corners, even in the

far north," says Rignot. Many of the outlet glaciers that flow down

fjords into the sea, which were "on the fence" about retreating or

advancing over the past decade, are now "starting to fall apart," he

says.

Danish Meteorological Institute

<Loading Image...

Illustration of the rapid expansion of ice melt on Greenland over just

two days in April 2016.

And they're moving fast. "The flow speeds we talk about today would

have been jaw-dropping in the 1990s," says Ted Scambos of the

University of Colorado's National Snow and Ice Data

Center. Greenland's Jakobshavn Glacier dumped ice into the sea at the

astonishing rate of 150 feet per day in the summer of 2012. The most

dramatic action in Greenland is simply from surface melting, as

temperatures there and across the Arctic have soared in the last four

decades. In 2012, Greenland lost a record 562 billion tons of ice as

more than 90 percent of its surface melted in the summer sun.

Many questions remain about the physics of Greenland's ice loss, such

as whether meltwater gets soaked up by a `sponge' of snow and ice, or

trickles down to lubricate the base of the ice sheet and speed its

seaward movement. Most modeling work has been about how Greenland's

melt tracks rising air temperatures; far less is known about how

warming waters might eat away at the edges of its ice sheet. Rignot is

part of a team now launching the Oceans Melting Greenland project

(with the intentionally punny acronym OMG) to investigate that. These

uncertainties make Rignot think that estimates of Greenland's melt -

contributing as much as 9 inches of global sea level rise by 2100,

according to the 2013 IPCC report - have been far too

conservative. Assuming that the Greenland ice sheet's demise "will be

slow is wishful thinking," Rignot says.

But most scientists say there shouldn't be too many serious surprises

about the physics governing Greenland's ice loss. Although the ice

sheet can be expected to steadily melt in the face of rising

temperatures, Greenland's ice cap shouldn't rapidly collapse, because

most of its ice sits safely on rock far above sea level. "Greenland is

more predictable and straightforward," says DeConto.

For fear of rapid, runaway collapse, the research community turns its

eyes south.

Antarctica is, for now, losing ice more slowly than Greenland. The

latest data from the GRACE project - twin satellites that measure mass

using gravity data - say Antarctica is losing about 92 billion tons of

ice per year, with that rate having doubled from 2003 to 2014.

The sizeable western half of Antarctica holds some of the

fastest-warming areas on the planet.

But Antarctica is vast - 1.5 times the size of the United States, with

ice three miles thick in places - and holds enough ice to raise global

sea levels by roughly 200 feet.

The larger, eastern half lies mostly above sea level and remains very

cold; researchers have typically considered its ice stable, though

even that view is beginning to change. The sizeable western half of

the Antarctic, by contrast, has its base lying below sea level, and

holds some of the fastest warming areas on the planet. "You look at

West Antarctica and you think: How come it's still there?" says

Rignot.

Warming ocean water licking at the underside of the floating edges of

the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet is eating away at the line where the

ice rests on solid rock. Much of the bedrock of the Antarctic slopes

downward toward the center of the continent, so as the invading water

flows downhill it seeps further and further inland, causing

ever-larger chunks of glaciers to flow faster into the sea. This

so-called "grounding line" has been eroding inland rapidly, in some

parts of West Antarctica at rates of miles per year. In 2014,

satellite radar images revealed just how vulnerable five massive

glaciers flowing into the Admundsen Sea are from this effect. And a

2015 paper showed that the same thing is happening more slowly to

Totten Glacier, one of the biggest glaciers in the east.

Such dramatic processes have been the bane of Antarctic modeling and

the reason why scientists have been loathe to put a number on sea

level contributions from a melting southern continent. Then in March

came a report in Nature that some say represents a step change in our

ability to do that. DeConto and David Pollard of Pennsylvania State

University put into their ice sheet model two basic phenomena:

meltwater trickling down to lubricate glacier flow, and giant walls of

ice (created when the ends of glaciers snap off) simply collapsing

under their own weight. These new modeling parameters gave DeConto and

Pollard a better understanding of past sea level rise events. For the

Pliocene era 3 million years ago, for example - when seas were dozens

of feet higher than today - older models estimated that a partially

melting Antarctic added about 23 feet to global sea level rise. The

new model increased Antarctica's contribution to sea level rise during

the Pliocene to 56 feet.

<Loading Image...

Satellite image showing sediment plumes from meltwater exiting

glaciers in Greenland.

Turning their model to the future, DeConto and Pollard project more than

three feet of sea level rise from Antarctica alone by 2100 - assuming

growing greenhouse gas emissions that boost the planet's temperature by

about 4 degrees C (7 degrees F). That is far more than the last IPCC

estimate in 2013, which projected less than eight inches of sea level rise

from a melting Antarctic by 2100, with a possibility for inches more from

the dramatic collapse of Antarctic glaciers.

Even DeConto admits that, under the model used in his paper, the timing and

pace of Antarctica's ice loss is "really uncertain" - it could be a decade

or two, or three or four, before these dramatic processes start to kick in,

he says. "The paper just shows the potentials, which are really big and

really scary," says DeConto. But Scambos and other observers call DeConto's

numbers "perfectly plausible."

Researchers could better pin down their models if they could track the rate

of sea level rise from polar ice sheet collapse in the past, but this has

proven hard to do. When seas rose a whopping 13 feet per century at the end

of the last glaciation (the current record-holder for known rates of sea

level rise in the past), much of the water came from an ice sheet over North

America, where there isn't one today. "I wouldn't use that as an analogue

for the future," says paleo-geologist Andrea Dutton of the University of

Florida, who wrote a recent review of past records of sea level rise. "But

it has important lessons for us nonetheless - that ice sheets can retreat

suddenly and in steps instead of gradually."

For a better analogue of what's going on today, researchers often look to

the last interglacial period, about 120,000 years ago, when temperatures

were about a degree warmer than pre-industrial levels and seas were 20 to 30

feet higher than today. Ice cores from Greenland have suggested that much of

that water must have come from the Antarctic. To find out just how fast sea

levels rose at that time, Dutton is now looking at old corals in Mexico,

Florida, and Australia; corals can be used to track sea level, since they

grow in shallow waters to capture sunlight.

--

Tesla Just Made Its Huge Model 3 Challenge Even Huger

WIRED, 05 May 2016 18:30Z

Elon Musk moved his desk. He now sits at the end of the production line at

Tesla Motors' factory in Fremont, California, and he's stashed a sleeping

bag in a nearby conference room.

Opinion:Tesla investors better be ready for wild ride -- CNBC

In Depth:Elon Musk Keeps Promising the Impossible. I Think I Know Why.

-- Slate Magazine

Winnipeg weather record set with 33-degree scorcher

CBC.ca, 05 May 2016 19:25Z

Winnipeg set a hot weather record on Thursday, when the mercury climbed to

33.2 C before 2 p.m.. The previous warm weather record for May 5 was set in

1926, when it was 31.7 C. The heat wave won't last long, though;

temperatures are expected to fall ...

Winnipeg hits 33 C, previous warm-weather record for May 5 was 31.7 C

CBC.ca, 05 May 2016 20:21Z

Manitoba broke 22 hot weather records Thursday, with the mercury climbing to

34.9 C in Winnipeg alone, making it the warmest place in Canada.

Alberta Declares State Of Emergency As Thousands Flee Massive Wildfire

ClimateProgress, 06 May 2016 8:18am

The Canadian province of Alberta declared a state of emergency Wednesday as

88,000 people in the city of Fort McMurray were forced to flee a fast-moving,

immense wildfire. The blaze has already destroyed 1,600 buildings, including

a school...

cold, rainy weather welcome after Tasmania's driest April on record

ABC Online, 05 May 2016 22:22Z

This week's rain has come with dam levels at 13 per cent after the driest

April on record. Hydro Tasmania has been drawing heavily on its storages

while the disabled Basslink electricity interconnector was not able to

import power.

'Armored Closet' Offers Tornado Safety Inside Your Home

CBS Local, 06 May 2016 03:23Z

Fort Worth (CBSDFW.COM). Depending on the home, it can be a challenge to

find a "safe-spot" during a tornado warning in North Texas.

More corals die in northern Great Barrier Reef

[Image] Coral bleached white in shallow waters off Lizard Island in the

Great Barrier Reef

ABC News, 06 May 2016 07:02Z

More coral has bleached and died in the northern section of the Great

Barrier Reef in the past month, new surveys reveal.